How 2020 Exposed the Holes in China’s Flood Controls

JIANGXI, East China — Inside Wu Youfeng’s inundated grocery store, boxes of instant noodles, pens, and other products bobbed on the water’s surface, just a few inches below the ceiling.

The 46-year-old and her husband spent 16 years building up the business in Youdunjie, a town in eastern China’s Jiangxi province. But the couple lost everything in early July as cascades of water surged through the streets.

When Sixth Tone visited Youdunjie July 15, most of the town was still submerged and Wu was navigating the streets in a blue boat. She estimated the floods had cost her family at least 1 million yuan ($140,000).

“It was difficult to start from a small store and turn it into a big one. Now, it’s all been washed away,” said Wu, carefully steering the boat past a clump of floating telephone wire. “I don’t know how our family will make a living for the next few months.”

Perched just a few dozen kilometers from China’s largest freshwater lake, Poyang Lake, residents in Youdunjie are accustomed to periodic water level surges. But the scale of this summer’s disaster caught the town off guard, with local flood defenses proving inadequate in the face of such extreme rainfall.

In Jiangxi province alone, the crisis has forced over 700,000 people to relocate and caused billions of dollars in damage. Nationwide, nearly 55 million people have been affected and 158 are dead or missing, with direct economic losses reaching 144 billion yuan.

For local residents and policymakers alike, the question is how towns like Youdunjie can protect themselves from megafloods like this in the future. In an era of climate change, extreme weather events are likely to become evermore common.

China’s flood-control authorities have been studying how to adapt to climate change, but it’s still difficult to predict how future changes will impact specific regions, according to Ran Qihua, director of Zhejiang University’s Institute of Hydrology and Water Resources Engineering.

This summer has made clear, however, that some areas of the country — especially less wealthy regions bordering smaller rivers — remain “weak links” during times of crisis, experts told Sixth Tone.

Youdunjie — located near a local river that feeds into Poyang Lake — is a case in point. Although the town reinforced its levees as recently as 2012 at a cost of 29 million yuan, the rising water breached the structures in early July, leading to five villages being inundated.

Huang Qiusheng, a 60-year-old Youdunjie resident, was part of a team of volunteers trying to shore up the levee with sandbags on July 8, when it became clear it would be impossible to hold back the floods. As more and more water penetrated the structure, Huang and his colleagues ran back to their homes to help their children and elderly relatives flee to higher ground.

“The water came too fast,” said Huang.

According to Fang Xuping, mayor of Youdunjie Town, the floods weren’t only caused by the heavy rain, but also by large volumes of floodwater discharging in upstream Anhui province, which flowed down into Jiangxi and further raised local water levels.

Lack of coordination among regional authorities is a major problem affecting efforts to prevent flooding along smaller rivers, said Ran, the Zhejiang University professor.

Since the historic floods of 1998, which killed over 4,000 people nationwide, China has invested huge sums to tame its major water sources. Massive infrastructure projects like the Three Gorges Dam were undertaken, downstream river embankments constructed, and flood storage and diversion areas identified.

Special “river basin committees” under the central government, meanwhile, plan and manage the flood-control policies along the country’s seven major river systems, helping to prevent conflicts emerging between upstream and downstream regions.

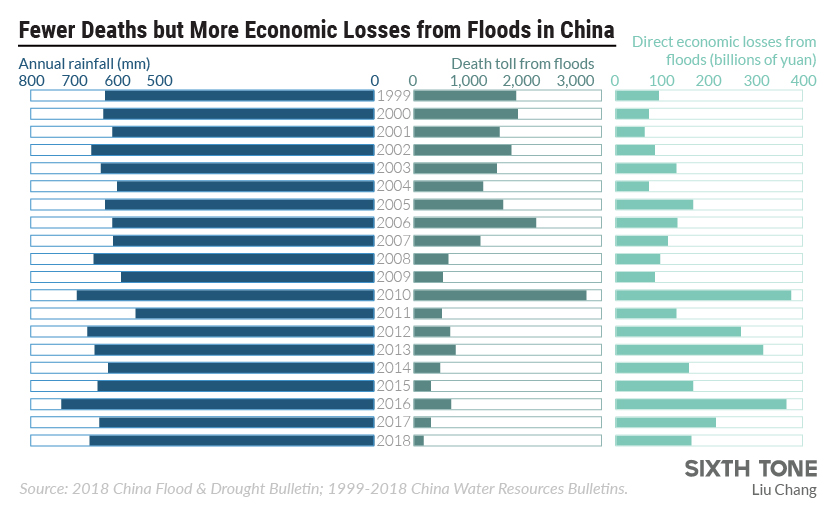

These measures have helped dramatically reduce the number of deaths caused by seasonal flooding over the past two decades. But similar mechanisms targeting small- and medium-sized rivers have yet to be developed.

In the vast majority of China’s river basins, the responsibility for flood prevention falls on individual local governments, leading to a patchwork of local projects with little overarching strategy.

“If I was the leader of Anhui province, I’d definitely want to ensure good flood control in Anhui, from engineering planning to construction,” said Ran. “But what about Zhejiang province? It’s basically irrelevant to me.”

Promoting greater cooperation among local authorities along smaller rivers should be the next priority, given that flood deaths occur mainly in these areas, Ran said. But creating such initiatives would be a daunting policy challenge.

“There are thousands of small- and medium-sized rivers,” said Ran. “It’s not something that can be accomplished in a short time.”

Regional inequality has also emerged as a barrier to flood-control efforts, leaving people in lower-income provinces like Jiangxi more exposed than those in wealthier regions.

“Disasters now have a greater impact than in the past, which has widened the contradiction in regional development,” said Cheng Xiaotao, a member of the Expert Committee of the National Commission for Disaster Reduction.

Lower-income provinces not only have smaller budgets for investing in flood-control projects; they often also struggle to implement emergency measures due to a shortage of working-age people, according to Cheng.

China’s rapid urbanization over recent decades has led to millions of people migrating from rural areas into the country’s major cities, leaving lower-income areas less able to maintain levees and conduct rescue missions.

In Youdunjie, local residents are calling on the government to provide support to those affected by the floods. The local government offered accommodation and meals for displaced villagers, officials told Sixth Tone, but further financial support would require funding from national-level authorities.

“It depends on central government policy,” said Fang, the town’s mayor. “Our capital reserves are limited … The lower-level governments generally have few ways of generating income by themselves.”

Another problem exposed by the floods has been the devastating economic losses suffered by communities impacted by flood-diversion measures.

Chinese authorities have increasingly adopted flood diversion as a strategy since 1998, when a series of major levee breaches caused catastrophic losses, according to Cheng. During this year’s floods, Anhui province used 11 flood diversion areas to mitigate damage to downstream regions.

But though residents in officially sanctioned flood-diversion areas are legally entitled to compensation if their homes are flooded, the payments often aren’t high enough to cover their damages, experts told Sixth Tone.

In other cases, communities aren’t sure whether they’ll receive any compensation at all.

As the severity of the floods became apparent in Jiangxi province, the provincial authorities took the drastic decision to open up dozens of local levees as an emergency flood-relief measure on July 13.

Local governments opened the water gates along 185 levees, releasing an estimated 2.4 billion cubic meters of floodwater. The move lowered the water levels on Poyang Lake by up to 30 centimeters, but it also left villages near the levees inundated.

In Xiaoyang, a village in nearby Duchang County, hundreds of villagers were moved into a local school in the hours before the gates were opened. When the floodwater was discharged, many of them lost their crops — and their livelihoods.

Gao Huazhen, 53, told Sixth Tone she’d recently returned to Xiaoyang after working for three decades in the garment workshops of eastern China’s Fujian province. She’d invested 200,000 yuan to start a rice farm, hoping to save up money to provide for her ailing son. Now, she isn’t sure what she’ll do.

“If the government can offer some subsidies, I can farm next year,” said Gao, sitting in her mud-stained living room, posters of Mao Zedong and Xi Jinping hanging above her. “If not, I’ll have to go back to work (in Fujian).”

Under Chinese law, however, residents in Gao’s situation aren’t guaranteed to receive compensation, since Xiaoyang Village isn’t located inside an official flood-diversion zone, experts told Sixth Tone.

In the future, the Chinese government will need to do more to inform people of the risk of farming or constructing housing in flood-prone areas, said Ran. Residents in Xiaoyang told Sixth Tone they had no idea the levees protecting their village would be opened up in the event of a severe flood.

In the long term, authorities should also focus on introducing flood insurance schemes, Ran added. The higher insurance premiums in flood-diversion areas will encourage people to move elsewhere.

At present, however, several Chinese regions have yet to establish flood insurance mechanisms, due to a lack of interest among insurers and local residents, according to Cheng.

Back in Youdunjie, however, people were focusing on more immediate concerns. The local water and electricity had been cut off, but some residents could be seen in their homes, pouring water from their second-story windows. The first floors were still completely underwater.

By the river bank, a group of residents sat and discussed rumors of looting during the night. Several said they’d refused to move into government shelters, saying they preferred to stay behind and protect their possessions.

A man surnamed Huang told Sixth Tone he’d been traveling into town by boat twice a day, to collect clean water. “I don’t want to leave,” he said. “There’s nowhere better than home.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: Two local residents paddle their boat through a flooded street in Youdunjie Town, Poyang County, Jiangxi province, July 15, 2020. Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone)